Back in 2017, while leading design and frontend at Taxi for Email, I wanted a way to make other developers aware of improper HTML as they were writing it.

My solution was a small JavaScript file called a11y-police.js that would detect some common issues — like a href="#" used in place of <button>, images with no alt text, etc. — and give the offending elements bright red outlines. Including the file only in the development environment would ensure that even if the issues weren’t corrected, customers wouldn’t see the outlines.

The problem was that we were working on a codebase that already had a few years’ worth of broken things piling up from moving fast. As soon as my script ran for the first time, pages were lighting up red. I saw this a huge win that validated my fledgling accessibility initiative. “See, look at all of the errors! It’s really important that we correct them and get this stuff right moving forward.”

What I failed to account for was that our time-poor engineers were up against ambitious sprint goals for which their estimates did not take into account dealing with unrelated markup issues. Refactoring HTML was, unfortunately but understandably, not a priority. They were busy — and now their localhost had a bunch of red outlines on it. I pulled down branches more than once to find the lines calling my JavaScript file commented out. Touché.

Turns out this wasn’t a unique solution. I’ve recently become aware of a number of similarly lo-fi HTML linters, some written exclusively in CSS:

- Eric Meyer’s Diagnostic CSS file

- Gaël Poupard’s a11y.css file

- GitHub’s accessibility.js

- Heydon Pickering’s Revenge.css file

- Ire Aderinokun’s CSS-based linter file

- These tools collected on CSS Tricks

- The #lintHTMLwithCSS Twitter hashtag started by Adam Argyle

- And many more

For some reason it never occurred to me to ditch the JS dependency and instead use the :not() and attribute selectors like that. The pure CSS approach is clever, and strikes me as most useful when a developer who is already well-versed in semantic HTML building or auditing a website. Good for catching yourself or assessing existing issues.

But what about larger teams on which knowledge across the stack can vary drastically? Can I expect a primarily backend engineer to know why img:not([alt]) is highlighted? If they can parse the rule mentally, do they know they should add descriptive text inside the alt attribute? And they should include the attribute but leave it empty if the image is purely decorative?

As a part of a broader initiative at Litmus — including forming and leading our frontend working group — I’m trying to apply my individual expertise at scale. To that end, a11y-police.js is back. (Except now it’s called HTML Crimes because ACAB and all that.)

This updated version is fundamentally the same as the original, with two important improvements.

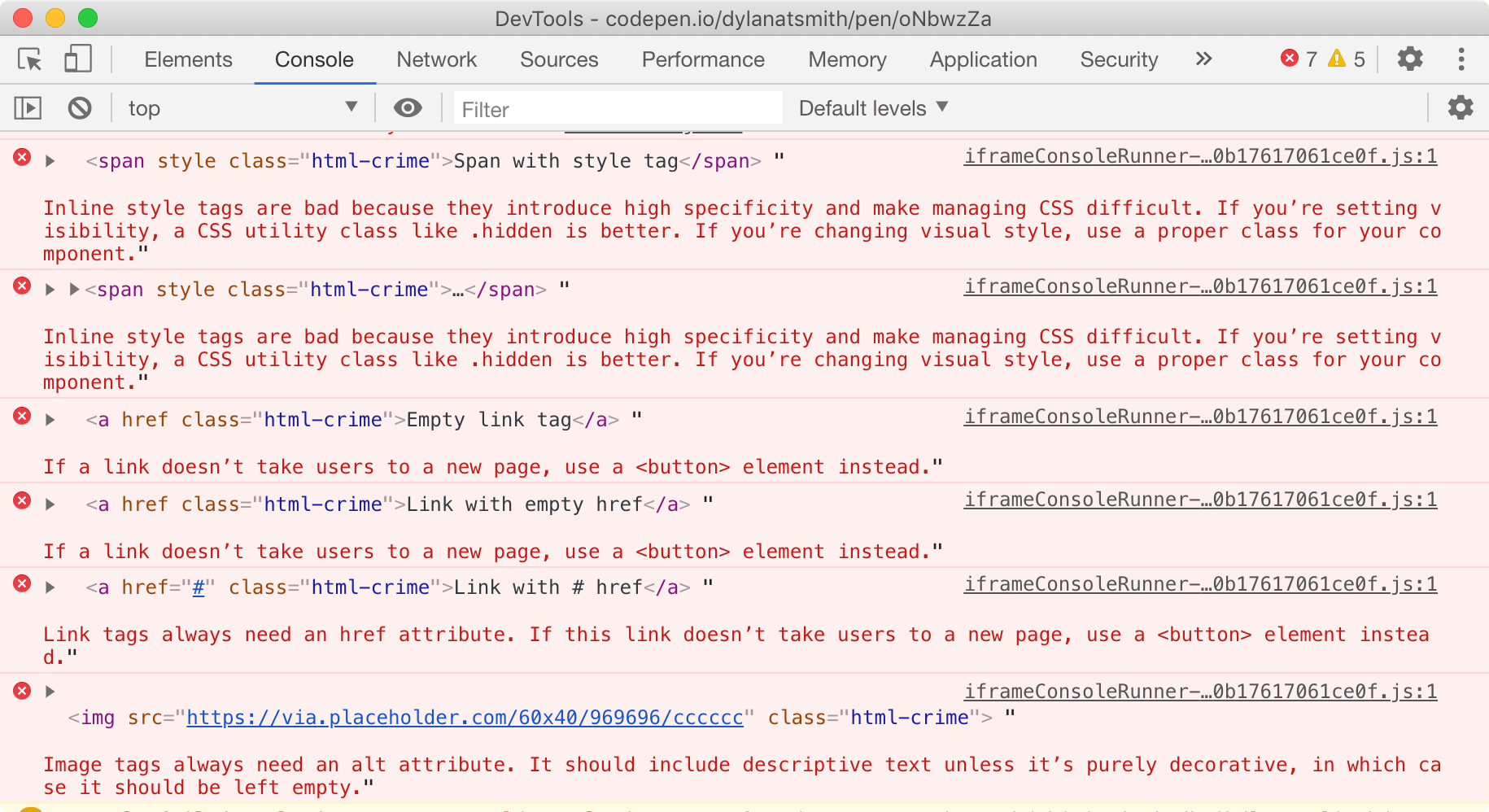

1. Errors are now logged to the console.

The first version added a data-crime-report attribute to an offending element to provide an explanation and tips for resolution. Now that helpful information is logged directly to the console, meeting developers where they are instead of making them dig through the inspector.

Even better, Nishiki taught me that logging an element in the console makes it possible to hover the error and highlight the element in the DOM.

2. I’m introducing it as an opt-in script.

Learning from my past mistake with the overwhelming number of errors, developers will have the option to run it manually to start with. I’d love for that to become a checklist item for us, but the reality is that it’s unlikely to see much adoption and we’d be better off running a linter at build time to achieve the same outcome.

That’s why I’ll spend some time myself tidying up the low-hanging fruit on high-visibility pages. Then I’ll consider the best way to make this a permanent fixture of our development process.

Looking further ahead, I’d like to expand the error coverage and explore the best way to flag and warn for a new category of potential issues instead of only critical ones. But most importantly, I’ll keep the feedback loop open to learn how I can best iterate to improve the developer experience.

Until I get a repo spun up, here’s the proof of concept on CodePen.